Recoveries: The Difference the Debt Makes (Not to Mention the Government’s Focus)

Earlier today, Glenn Reynolds linked to an American Enterprise Institute post by James Pethokoukis, drawing on charts from economist John Taylor showing that the United States economy hasn’t been returning toward where it would have been without the crash, and that this is unusual for prior downturns.

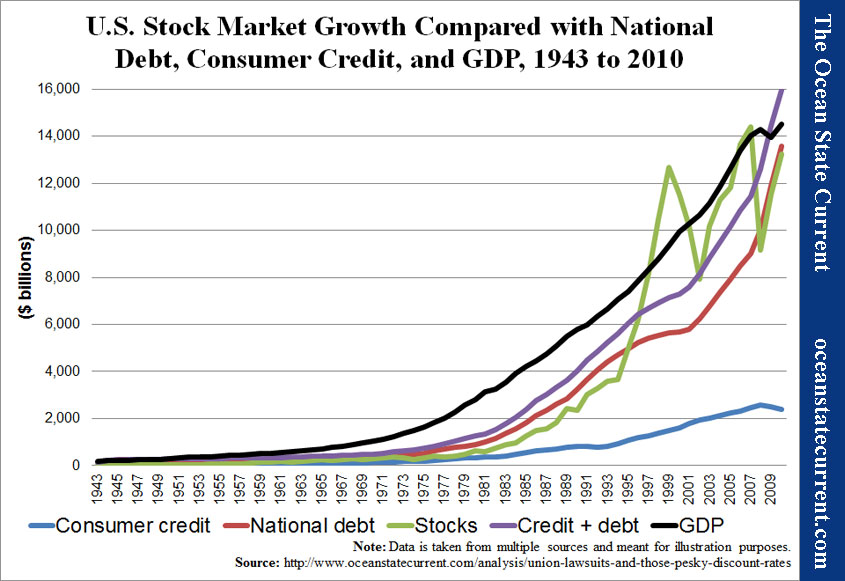

The reasons, I think, can be inferred from this chart, which I created with a view toward answering the question of whether it’s reasonable to continue expecting 7-8% returns on pension fund investments:

I’ll be updating this chart and expounding on the conclusions that I draw from it in the near future, but for the moment, compare the situation that President Reagan faced upon recovery from his downturn in the early ’80s and the situation that President Obama faced. In very broad strokes, the debt and monetary outcomes have been similar, at least in effect. Both administrations experienced low inflation and an acceleration of government debt.

The expected effect ought to be to fill the market with dollars that can be put to work without simply driving up prices. But a clear lesson of history has to be considered: context and circumstances matter.

The first difference between the two was that Reagan was a deregulator, which in conjunction with tax breaks greases the tracks for borrowed money to get into the economy. By contrast, Obama has cut deregulation out of the Reaganomics model and lunged in the opposite direction in a multitude of ways, perhaps most notably with ObamaCare. In addition, rather than reducing the disincentive to produce that regulation creates, Obama has reduced the incentive to produce by expanding entitlements.

The second difference is that the stock market was significantly more constrained before the combination of regulatory easing of the finance industry under President Clinton and the simultaneous push to provide housing loans to people who were, in effect, borrowing wealth from a future that they didn’t have. Considered separately from the risky mortgages, deregulation of the market isn’t necessarily bad, because as the green line indicates, it draws non-government resources into productive use.

But with the bailouts (which Fannie and Freddie had already made implicitly probable), the risk that the financiers had undertaken effectively became a short-term loan to taxpayers, payable when it looked like the stock gamblers were going to lose their bets.

The third difference (probably the greatest) is the ratio of national debt to GDP. When Reagan took office, the debt was about 32% of GDP. When Obama took office, it was around 85%. Put differently, in the early ’80s, 68% of the money in the economy came from other sources than the future taxable economy; in the late ’00s, only 15% did.

The combination of these factors is why the economy turned public debt into GDP growth for Reagan, but not for Obama. During the five years before Reagan left office, national debt grew by $1.29 trillion, but GDP grew by $1.55 trillion, a 21% premium. In the five years leading up to 2011, debt grew by $6.28 trillion, but GDP grew by only $1.70 trillion, or -73%.

Supporters of President Obama would have some ground to turn to their “it’s Bush’s fault” defense. Had his circumstances, upon entering office, been the same as Reagan’s, he might have had more success. However, two factors put the continued economic suffering squarely in his lap.

- The failure to deregulate shows that the administration either does not fully understand Reagan’s lesson or (more likely) was so driven by ideology and the opportunity of holding the White House, the Senate, and the House that it didn’t care.

- If economic circumstances never changed, it wouldn’t really matter who holds office. A committee of technocrats could pull all the right levers to get things moving. The mark of an effective leader is that he or she can assess circumstances as they exist and act accordingly, and it is the job of the President to prioritize issues for the nation.

The appropriate conclusion is, therefore, not new: President Obama has not paid as much attention to the economy as he should have, and he therefore did not recognize the dire necessity of sacrificing his political agenda for the sake of economic growth or observe that the national debt was not flowing into productive activities, but into making his friends on Wall Street whole.