Let’s Acknowledge RI’s Real Problem

The same people who brought Rhode Island Democrat Governor Gina Raimondo’s failing economic development policy are now out with a new report fretting that only a few metropolitan areas in the country are seeing growth in the seemingly-all-important “innovation industries.” As Eduardo Porter summarizes in the New York Times:

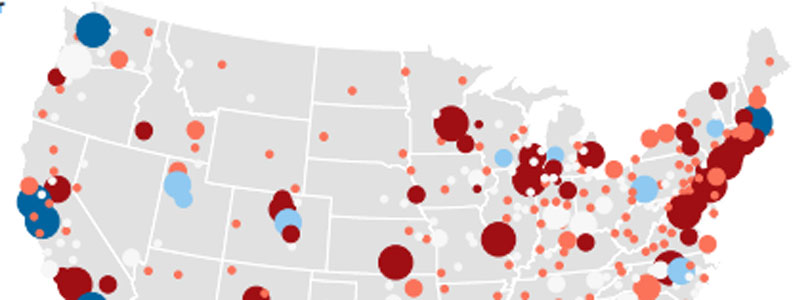

The report is by Mark Muro and Jacob Whiton from the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, and Rob Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a research group that gets funding from tech and telecom companies. They identified 13 “innovation industries” — which include aerospace, communications equipment production and chemical manufacturing — where at least 45 percent of the work force has degrees in science, tech, engineering or math, and where investments in research and development amount to at least $20,000 per worker.

The authors argue that a broad federal push is needed to spread the business of invention beyond the 20 cities that dominate it. “Hoping for economic convergence to reassert itself would not be a good strategy,” Mr. Muro said.

No matter the problem, the folks at Brookings always have the same solution. From their report:

Neither market forces nor bottom-up economic development efforts have closed this gap, nor are they likely to. Instead, these deeply seated dynamics appear ready to exacerbate the current divides.

We should be grateful that the authors are being so straightforward. What they want is “top-down economic development.”

This is exactly backwards. When innovation starts and takes hold in a region — for whatever reason — it generates a number of measurable markers. These might be numbers of workers or jobs in certain industries or types of investments or even specific government policies. But it can’t be said (at least as a blanket statement across the nation) that these things were the cause.

Take government policies, for example. If the specific circumstances of an area are conducive to some particular development (because of geography, workforce, accidental mixes of personalities, or whatever), people will increasingly push for changes to help it along, and local politicians will be able to see the tangible advantage. So, maybe copying those policies elsewhere will have the same effect, or maybe it won’t, because the policies were more of a reinforcing effect than a cause.

We’re talking about every factor in a local society, which puts analysis beyond the ken of analysts. These things happen organically. To capture this wind in a bottle, therefore, requires freedom for people to experiment (and profit), which extends from regulatory requirements to the costs that government imposes. Otherwise, as I argued when the Brookings show came to Rhode Island, you could just reinforce existing problems.

Indeed, look at the three-page table on page 85 of the new report. It shows the change in employment in “innovation industries” in the 100 largest metropolitan areas from 2005 to 2017. Providence is in the bottom 15 in percentage terms, tied with eight other metros, having lost 4,672 jobs in this sector. The next table shows 35 “potential growth centers,” with an “eligibility index” for innovation development, and Providence doesn’t make the list.

Only three years have elapsed since Brookings made its recommendations to Rhode Island, so it might be unfair to saddle the organization with our lost innovation employment. That said, we should take note that three years of their prescriptions in a growing national economy was not enough to keep the Ocean State away from the bottom of the list. We would also be justified in wondering why Brookings advised us to focus on something that it is now suggesting we might not be “eligible” to do.