The Growing Upper Middle Class and Healthy Redistribution

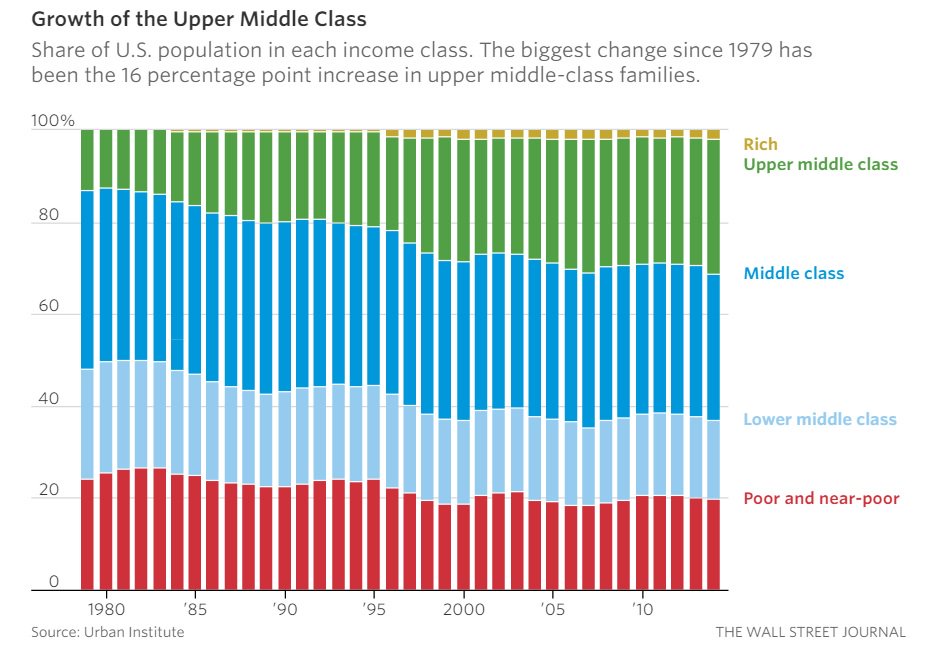

In the election-season crucible, income disparities are difficult to discuss rationally, but I think this chart — which James Pethokoukis posts on his AEI blog from a Wall Street Journal article using data from the left-leaning Urban Institute — can help:

Yes, the middle-middle class has been shrinking, but so has the lower-middle class and the poor-and-near-poor class, too, and not because people are stagnant or losing ground. The movement is upward.

The key question is how the researcher, Stephen Rose, defines the classes. Obviously, income quintiles will show no changes in relative size, and other ways of dividing them up could construct a false sense of improvement. Rose defines the upper class, basically, as those people who consider themselves “upper class,” which was roughly 2% of the population during the end-year of that chart. The upper middle class, meanwhile, is defined relative to the poverty level, specifically five times that level.

So, the chart shows that the proportion of the population that is that far away from poverty has more than doubled since 1979. How can that not be a good thing? The Left will argue that the gap between the top two groups and the lower three has been growing (or something like that), but if an economic system is making everybody wealthier, the fact that the rate of improvement is uneven might be an inevitability, rather than an argument against that system. The burden isn’t to show that wealthier people have benefited more, but to show that it’s possible to raise everybody up without having that happen. The world’s experience suggests that it isn’t.

Our economic system is not perfect and leaves much room for improvement (particularly on the morality side of the ledger), but when something is functioning, our concern should be to adjust it while not undermining it entirely. The impulse that progressives expose when they talk about the size of the middle class is the urge to push everybody to the same level, even though that will mean pushing half of all people down.

This approach has a fatal flaw: If we take money from the top of the chart and give it to those at the bottom in order to bring them up, those at the top won’t do the sorts of things that have grown the economy for everybody, leaving less money to redistribute.

In contrast, if we continue to allow people to do the sorts of things that earn them money and attack the disparities through the culture, being able to voluntarily redistribute one’s money will become a reason to strive, rather than a reason to coast.