Inspectors General and the Corrupt Edifice of Big Government

Juxtapose two articles published in the Washington Post, recently:

- Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz is making headlines based on his apparently groundbreaking decision to post online summaries of his office’s investigations involving higher-level employees in the agency (with no names included).

- U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D, RI) appears to want the Justice Department to investigate individuals and groups who express skepticism about radical climate-change activism under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO).

According to reporter Lisa Rein, the nearly four score inspector general offices throughout the federal government “as a rule don’t make their investigations public,” except to comply with Freedom of Information Act requests. Consequently, the public has a sense of “poor accountability in government,” with rule-breaking employees shuffled around or led to gentle retirement.

In Whitehouse’s Rhode Island, legislation to create an inspector general’s office for the state has become an annual bill that some suspect to be marked “dead on arrival” in invisible ink. The concept enjoys rare agreement between progressives and conservatives, but for the most part, it’s a topic of conversation when it’s convenient for government officials to bring it up.

If Mr. Horowitz’s efforts are any indication, though, even if inspectors general publish reports online for public consumption, they’re barely scratching the surface of an enterprise — big government — that could do with a thorough RICO investigation, itself.

Naturally, Senator Whitehouse’s call to use government to disrupt the activities of organizations with which he has political differences could be exhibit A. As he ends by saying, he doesn’t “know whether the fossil fuel industry and its allies engaged in the same kind of racketeering activity as the tobacco industry,” but he’d sure love access to information about their inner workings.

Innuendo and calls for transparency are powerful tools for a more subtle sort of racketeering.

Campaign finance law in Rhode Island serves a similar function. Under legislation recently signed into law by Governor Gina Raimondo (D), any person running for public office in the state, from the smallest town budget committee to the governor’s office, has to maintain a separate bank account for campaign donations and cannot “comingle” personal funds.

That may sound like a minor inconvenience for the privilege of running for public office, but only under the assumption that candidates are professionals cooperating with parties and the political establishment. Independent candidates (from whom Rhode Island Republicans are difficult to distinguish) can easily become discouraged or bogged down with details and targeted for official complaints if they miss a dot on this or that “i.”

A few days before a suburban special election to fill a surprise opening for representative to the state General Assembly, the chairman of the state Democrat Party announced an ethics complaint against the Republican and two independent candidates for missing the deadline to send in a financial statement. That news, by the way, was followed by anonymous postcards linking the Republican with extreme photographs from Tea Party rallies (apparently from other states). The Democrat won by 88 votes (4% of the total).

Meanwhile, the state’s Senate Majority Leader, Dominick Ruggerio (D, North Providence, Providence) collects nearly $200,000 in salary and other benefits from a division of the New England Laborers union and recently submitted legislation to create a property tax deal for new commercial developments in an open area of Providence. The city, it seems, isn’t moving quickly enough to cut deals in favor of developers who will provide union labor with contracts.

A casual observer of Ocean State politics might conclude that government officials consider a local candidate who accidentally spends campaign money on groceries to be a threat to democracy, while labor unions that work for the election of their own employees and members to state and local offices are simply part of the democratic process.

Rhode Island is a state in which it is arguably legal for legislators to sell their votes on legislation. It’s a place where public-sector unions can always turn to the state government for a redo when local voters finally declare that they’ve had enough at the local level. It has a government in which an obscure bureaucratic planner can commit the state to federal housing requirements, and an executive order and astonishingly bad projections can force the people into a new paradigm for healthcare.

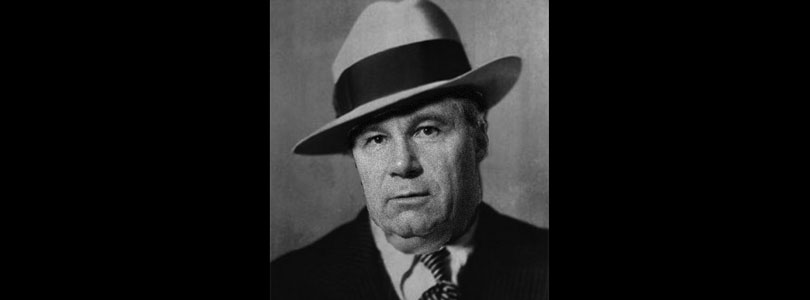

Mobster Al Capone was famously convicted, finally, on the procedural charge of tax evasion. Inspectors general may not be able to bring down the entire edifice of big-government corruption, but maybe they can give the public a sense of the sort of organization they’re dealing with.

In the meantime, dissenters will have to hope that they can fill out enough forms (and make enough campaign donations) to protect themselves from the likes of Sheldon “The Lefty” Whitehouse.