Rhode Island’s Unique Way Out of the Bottom Three

For many months, Rhode Island has been exchanging places with two other states for worst, second worst, and third worst official unemployment rate in the United States. February marked the milestone of Rhode Island’s breaking free from the dance. The Ocean State’s 9.4% unemployment rate tied with North Carolina for fifth worst, behind California, Nevada, and Mississippi (all 9.6%) and Illinois (9.5%).

But the numbers deserve a closer look.

People who are considered “unemployed” have told surveyors that they are unemployed and have looked for work within the past month. The labor force adds these people to the total number of people who say they are employed (even part time). The unemployment rate is the unemployed people’s percentage of the total labor force.

Consequently, the rate can go down not just because more people find work, but also because fewer people are bothering to look. Therefore, as the employment outlook improves, the unemployment rate might actually go up, because more people come to believe that it’s worthwhile for them to kick off or resume their job searches.

That is arguably what is happening for Rhode Island’s long-time companions in the bottom three: California and Nevada. Since December, California’s number of people who say they are employed has gone up 0.6%, but the total number of people in the labor force went up 0.5%. In Nevada, employment went up 0.3%, and the labor force went up 0.1%. In Rhode Island, by contrast, employment is up 0.1%, while labor force is down 0.3%.

This means that Rhode Island’s unemployment rate has fallen from 9.9% to 9.4%, while California and Nevada, which both had stronger employment growth, only went from 9.8% to 9.6%. If Rhode Island’s labor force had just held steady, its unemployment rate would still be a last-place 9.8%. If its labor force had increased as much as California’s, it would be back over 10% unemployment, based on its current employment.

By contrast, if California and Nevada had lost labor force like Rhode Island, their unemployment rates would be 8.9% and 9.2%, respectively.

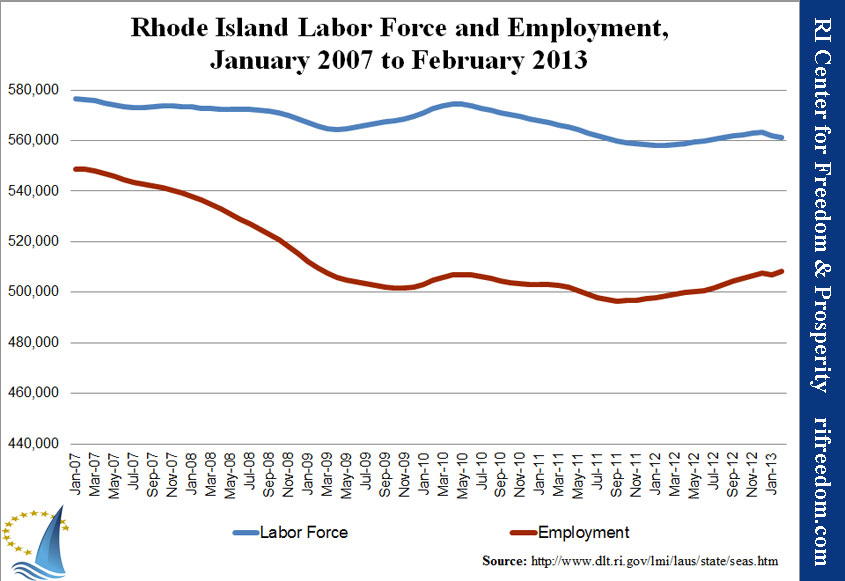

The following figure gives some visual sense of what’s going on in Rhode Island. The blue line shows the labor force, which is nearly the smallest it’s been since early 2005, while the red line shows employment, which is still a long, long way from where it was when the recession began, here.

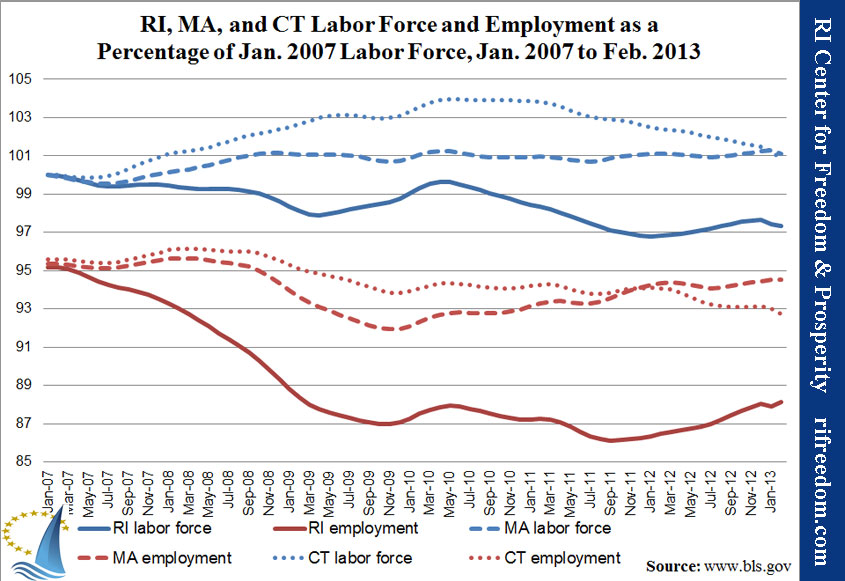

Putting these lines in the context of our neighbors, Connecticut and Massachusetts, produces another cynical silver lining: If Connecticut continues in its rapid decline while Rhode Island manages to hold relatively stagnant, the Ocean State may begin to be a little less conspicuously woeful in its region.

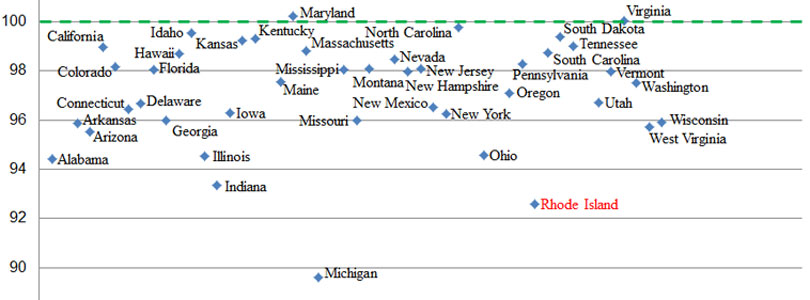

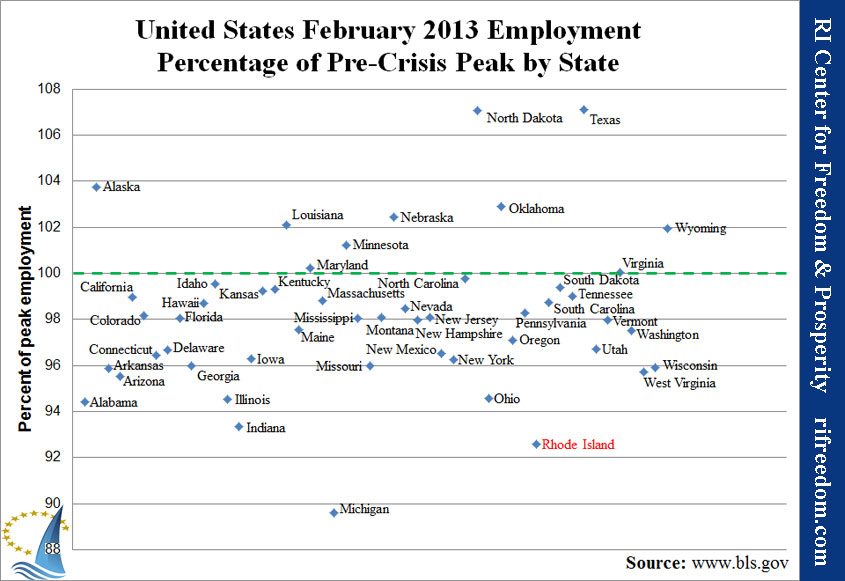

On a month-to-month basis, stasis is pretty much the rule across the country, although Texas and North Dakota continue to float well above their pre-recession employment peaks. Rhode Island remains stuck as second farthest from its own peak.

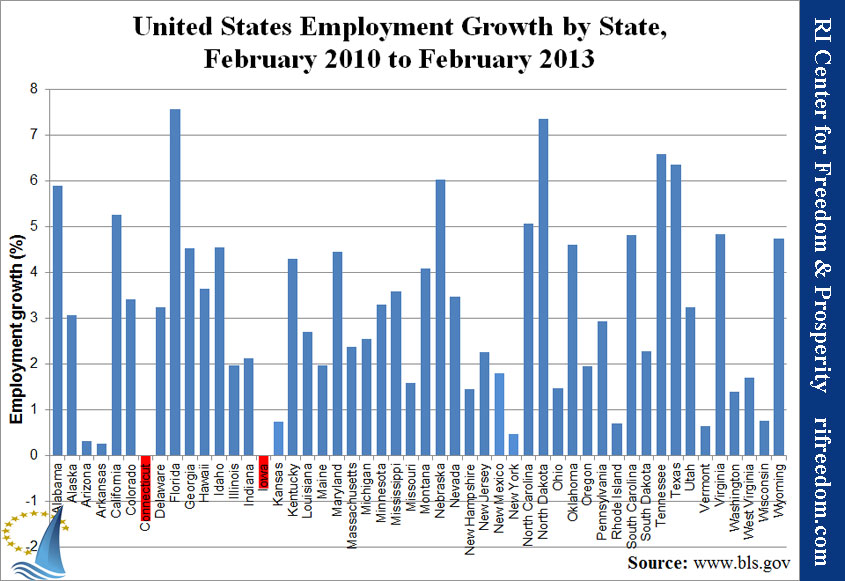

Similarly, state-level employment numbers since the end of the national recession in February 2010 show general stagnation, viewed from month to month. However, they do give some context to Rhode Island’s current rut. Although it is tied with North Carolina when it comes to unemployment rate, the number of employed residents, compared with the recession’s trough, does not compare.

This, again, shows the effect of labor force size on unemployment rate in a way that doesn’t necessarily reflect the health of the job market. A 9.4% unemployment rate means something different when a state has nearly recovered to its peak employment and has added 5% to its employment in a few years, versus a state that is nearly 8% below its peak and has grown employment less than a percent over three years of recovery.

Putting all of the charts together, Rhode Island’s path out of the worst three when it comes to unemployment rate suggests an urgency to find its way out of the worst three when it comes to distance from employment peak. As the scatter chart above shows, Rhode Island’s company on the latter list is Indiana and Michigan. Both of those states took dramatic action, last year, by becoming right to work states.

It isn’t necessary for the Ocean State to pursue that particular policy, but residents should be looking for something that will improve the statistic by improving the actual health of the economy. Eliminating the sales tax would be one option.