The Ever-Growth Unfunded Liability

Pension liability is the story that just keeps growing. And the point that seems to be working its slowly permeating way through public awareness is that even the eye-popping numbers that have been frightening policymakers for a few years are understated.

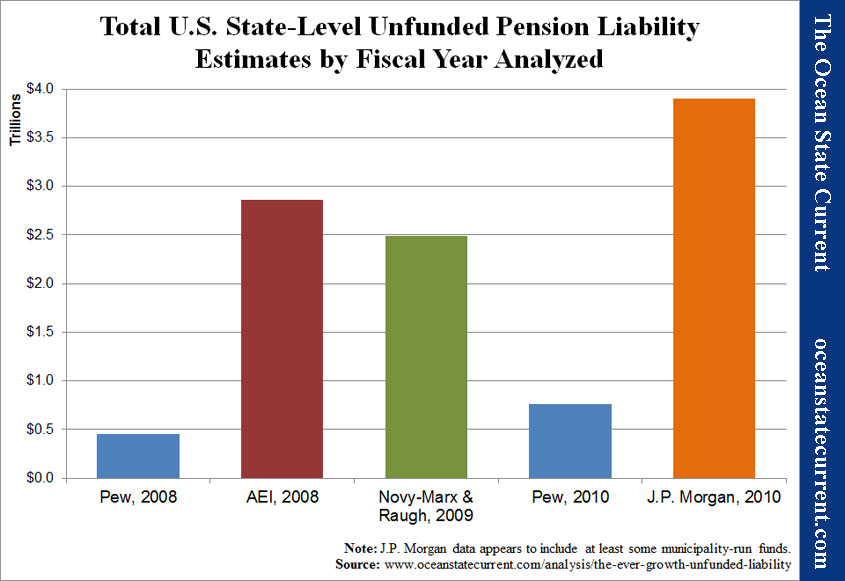

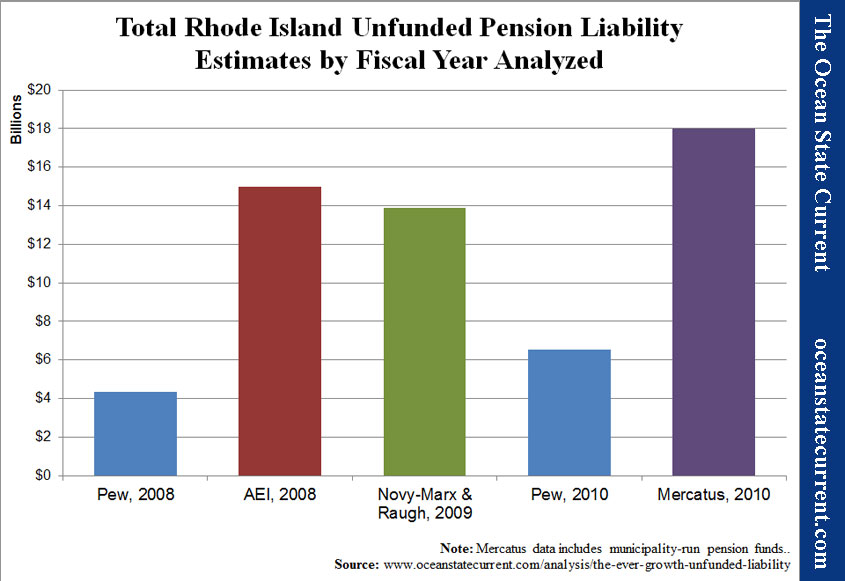

In 2010, the Pew Center on the States released The Trillion Dollar Gap, assessing the states’ unfunded pension and other post-employment benefit (OPEB) liabilities. On pensions alone, Pew found the states to have a total unfunded liability of $452.2 billion. To be clear, that’s the money that the states would need to add to their portfolios immediately to cover pension promises in the future. The total promises are many times greater. For Rhode Island, Pew put the unfunded liability of all plans administered by the state (including the Municipal Employees Retirement System, or MERS) at $4.4 billion.

Last March, State Budget Solutions put Pew’s numbers alongside two alternate measures of states’ pension liabilities. Pew used the same “discount rates” as the states, meaning the rates of return that states assumed they’d earn on their investments as free money flowing into the fund. That’s a point of contention because states tend to assume that their earnings will be roughly equivalent to somewhat risky stock investments. Increasing numbers of economists are pointing out that a guaranteed benefit like pensions ought to be valued using less-risky investments, such as Treasury bonds.

According to State Budget Solutions, Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) argues that public pensions should be handled under the same financial terms as private-sector funds. Under his calculations for FY08, the states’ total unfunded liability was actually $2.9 trillion, with Rhode Island accounting for $15.0 billion of that.

Another alternative that State Budget Solutions presents is to use zero-coupon Treasury yields, which do incorporate some calculation of risk but are effectively default free. On that basis, University of Chicago Professor Robert Novy-Marx and Northwestern University Professor Joshua Rauh put the FY09 unfunded liability at $2.5 trillion, with Rhode Island accounting for $13.9 billion.

In the past few years, however, pension funds have not experienced anywhere near the returns that their administrators assumed, and many have not made required payments. This week, when Pew updated its numbers using FY10 data, it found a large increase in the shortfall. At that point, the acknowledged national unfunded liability was $757 billion. Rhode Island’s was $6.6 billion.

An alternate assessment of FY10 data for Rhode Island comes from Eileen Norcross and Benjamin VanMetre of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, developed in cooperation with the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity, the Ocean State Current’s parent organization. Using Treasury bonds to mirror private sector insurance rates, Norcross and VanMetre valued Rhode Island’s FY10 unfunded liability at $18.0 billion.

It is important to note that this number also differs from other assessments in that it incorporates the liabilities of pension funds administered by municipalities. For perspective, the total state and local unfunded liability as reported by the various state and local funds at the time was $9.3 billion.

At the national level, another recent number comes from Fox Business news reporter Charlie Gasparino. Apparently, municipal debt underwriter J.P. Morgan studied state and municipal liabilities in March 2011, but decided that public release of the data would upset governmental clients. Citing a leaked copy of the study, Gasparino puts all states’ unfunded liabilities at $3.9 trillion.

It isn’t clear what fiscal year that number covers or how thoroughly it incorporates pensions controlled by cities and towns. However, looking at Gasparino’s articles in on FoxBusiness and in the New York Post, one can infer that it covers FY10 and does include at least some city-run plans.

The following charts present the above numbers in graphical form.

In the case of Rhode Island, it’s important to acknowledge that all of these numbers are prior to the pension reform that General Treasurer Gina Raimondo spearheaded through the General Assembly in the fall of 2011. That reform shaved roughly $2 billion from the assumed liability and lowered the total a bit more through reamortizing the debt for six additional years. Still, the salient lesson of these comparisons is the sheer size of the difference between various methods of calculating liability.

With a five-year average investment return of 2.28%, the state’s pension fund has been in line with or underperforming the assumptions used to generate the highest estimates of liability. If that continues to be the case, the “unprecedented reforms” of last year will quickly prove insufficient.