Thoughts on Cardinal Sean O’Malley and the Evangelization of Whom

On day one of the 2015 Portsmouth Institute conference, on “Understanding the Francis Papacy,” the critical question that began to assert itself between the lines, so to speak, was whether the pope has correctly assessed the world as it is currently poised and, therefore, his role in it.

With Anna Bonta Moreland’s opening speech, the question took the form of whether the world is rapidly approaching or just beginning to recover from some sort of catastrophe. An interfaith panel brought in the intermingling of politics and religion. Next, Ross Douthat made it a question of dialogue, and whether Pope Francis has a full sense of the consequences of goading us all into open discussion of our differences, with the important judgement call being whether he’s signaling the assured victory of a particular faction.

At that third link, I suggested that Catholics could perhaps learn from the experience of American conservatives. Specifically, Catholics should be prepared in the event that Pope Francis has the same effect that President Obama has had on his devotees, who are lunging forward on their ideological crusade with reckless abandon, confident not only of their righteousness, but also of their ultimate success.

Another lesson that conservative Americans could offer to Catholics derives from their decades of experience observing American progressives’ playing a game of bait and trap. In the name of helping “the little guy,” “minorities,” and “the disadvantaged,” (mostly) wealthy whites have managed to create barriers to less-elite whites and others, lest they threaten their power. Common practical examples would be minimum wages and licensing that serve to raise the barrier to entry for smaller, more-driven competitors. The apotheosis may be the redefinition of marriage, which removes a strong mechanism by which individuals and families can move themselves forward economically as they build themselves up morally.

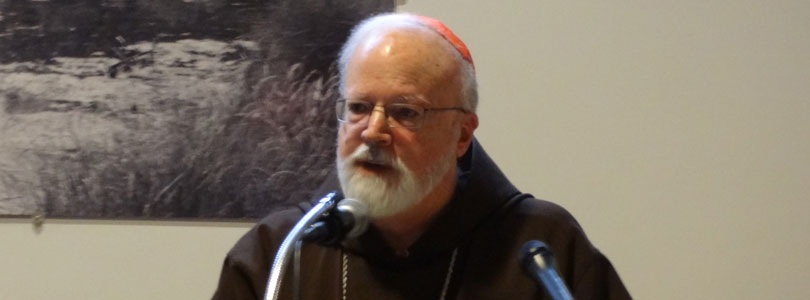

Listening to Cardinal Sean Patrick O’Malley of the Archdiocese of Boston (video below), something similar came to mind. O’Malley mentions that Francis was drawn to the Jesuit order because of (1) its missionary spirit, (2) its sense of community, and (3) its emphasis on discipline. He also cited Francis’s affection for Caravaggio’s “Calling of St. Matthew.”

The telling observation is that Cardinal O’Malley emphasizes Jesus’ position in that painting: pointing at the tax collector. The human profundity of the image, though, lies with the reactions. Matthew is either the surprised man in the center, still reaching across the table to grab some money (as Pope Francis seems to have indicated), or he is the young man who stares doggedly down at the coins on the table. Either way, we see reluctance to transform into a new life.

O’Malley goes on to convey Francis’s belief that the “entire history of our redemption is marked by the presence of the poor,” and so it is. But the point that seems to get lost in modern discourse is that there is no line of humanity between the poor and those called to help them. The comfortable are in just as much need of pastoral care as the discomfited.

That isn’t a complaint that religious figures should pay more attention to and respect for the sensitivities of poor little rich folks; it’s a suggestion that thriving first-world people need a deeper engagement than the call to indulge their paternalistic impulses. Cardinal O’Malley paraphrases something that the pope used to tell seminarians: that someone who can make the Catechism simple enough for children to understand is a wise person. But poorly or un-catechized adults don’t understand as children, and sophisticates may not take the call seriously if it is spoken in nursery rhymes. Complexity doesn’t make the Christian message go away; it enriches it.

In this context, O’Malley’s mention of the “moralistic therapeutic deism” — in which young Westerners believe religion is about “being nice and doing good,” while retaining God as an emergency go-to to answer prayers — comes across more as a chastisement of people who ought to know better, rather than what it should be: an identification of a particular spiritual challenge. As St. Matthew quotes Jesus in his Gospel book (19:24), “it will be hard for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of heaven.”

It stands to reason that they will need the most help. To the extent that the Church is relying on them to extend their own advantages to others to the point of self sacrifice, evangelizing the comfortable is an indispensable step.

They need to be shown that the morality that they know to be true is more fully true within the light of Christ. They need to see that the Church isn’t just another charity with a sales pitch, that it is concerned with them. Their salvation is not assured simply by going with the crowd and believing in the right causes. Rather, the disposition of their souls depends upon their own intricate relationship with the world and its Creator.

Christians sink from lessons that sound like selfishness, but the main character in the drama of “The Call of St. Matthew” is… St. Matthew. Again, his Gospel quotes Jesus as calling the disciples by saying, “I will make you fishers of men” (4:19). Jesus doesn’t beckon them with the images of the people for whom they can sacrifice themselves; he doesn’t say, “the world needs you.” Later, when Jesus explains to them about putting others above themselves, the instruction is how they can make themselves greater than they are in the eyes of God.

Too often — even within the half-hour of the cardinal’s speech — the impression is that the poor and the immigrant are to be handled gently and catered to, while those who are not struggling in such material ways must be shaken awake to the point of compassion. For the first, the message sounds like “God loves you, and those people owe it to you to prove it”; for the second, the message sounds like “those people need you, and you sin if you don’t respond to them.”

Cardinal O’Malley said that, “without mercy, the truth can be cold, off-putting, and can wound; the truth isn’t a wet rag that you throw in someone’s face.” This is as true for those lost generations in the West as it is for those who struggle the world over.

The cardinal and pope both know this, of course, but I wonder if they assume too much common ground to exist between themselves and the communities to which they’re preaching — calling people to be missionaries who should actually be missionaries’ subjects. The New Testament doesn’t begin with the Beatitudes; it begins with the Word and the promise. Maybe evangelization should begin the same way.

A global message, as Pope Francis cannot avoid transmitting, can be heard differently by people in different conditions, and with the help of the Holy Spirit, people can hear a single statement in precisely the way they need to hear it. Still, the speaker has the challenge and the responsibility of ensuring that he speaks from the Spirit’s inspiration, not that of the intellectual habits of an elite culture or a secular ideology that has been woven throughout international institutions.

Too many people on both sides of the world’s ideological divide are hearing the secular messages. Some like it, and others don’t, but it isn’t clear that victory for the former serves their souls any better than defeat for the latter.