U.S. Grant and the Left-Right Lines

Two lines of debate in the battle of Left versus Right cross frequently.

One is the question of whether history has an inexorable pull toward which it progresses, making it possible for there to be a “right side” of history that one can predict beforehand for a given issue. The other is whether one’s side on the issues of the day offers a direct parallel to the sides that one would have taken having born at another period in history.

An excellent example is the assumption that those who see themselves as advocates for minorities (often seen by the other as cynical panderers) would have been on “the right side” of the battle over slavery. That belief is held despite the fact that progressives’ history has run through such intellectual marshes as support for eugenics, or forced rules on reproduction, particularly of minorities, for the good of society.

The flip side, usually offered as an accusation against their opposition by those who buy into the notion that history has continuous “sides,” is that those of a more conservative bent by today’s scale would have held hands with supporters of American slavery. Intellectually, for example, conservatives support federalism for many of the nation’s more intractable problems, and in the progressive mind, federalism was a mere pretext among nineteenth century racists to continue their evil practice.

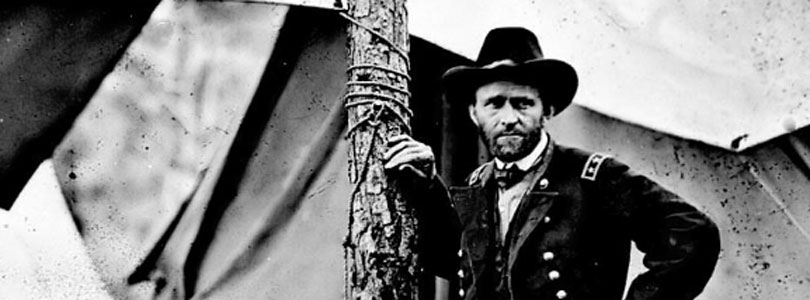

I bring this up, now, because I’ve just finished listening to a book-on-mp3 reading of President Ulysses S. Grant’s Personal Memoirs. I mentioned the feat on Twitter, and WPRI’s Ted Nesi directed my attention to a March 2010 post by progressive blogger Matthew Yglesias, suggesting that Grant’s record on civil rights made him a target for conservatives for replacement on the fifty-dollar bill:

Of course part of the issue here is that conservatives don’t care about civil rights. They fought it tooth and nail until 1964-65 and then suddenly in 1966 stopped supporting white supremacy and simply started taking the view that basic civil rights is all well and good but now the left is taking things too far. They don’t think slavery was a big deal and the only racism issue they recognize is the fear that someone, somewhere, is being too hard on white folks in the name of anti-racism run-amok.

One could spend quite a number of words picking apart the ideological assertions in that paragraph, but the aspect that’s relevant to the topic at hand is its contrast with a sort of conservative, federalist perspective that Grant attributed to himself in his book:

The cause of the great War of the Rebellion against the United Status will have to be attributed to slavery. For some years before the war began it was a trite saying among some politicians that “A state half slave and half free cannot exist.” All must become slave or all free, or the state will go down. I took no part myself in any such view of the case at the time, but since the war is over, reviewing the whole question, I have come to the conclusion that the saying is quite true.

Slavery was an institution that required unusual guarantees for its security wherever it existed; and in a country like ours where the larger portion of it was free territory inhabited by an intelligent and well-to-do population, the people would naturally have but little sympathy with demands upon them for its protection. Hence the people of the South were dependent upon keeping control of the general government to secure the perpetuation of their favorite institution. They were enabled to maintain this control long after the States where slavery existed had ceased to have the controlling power, through the assistance they received from odd men here and there throughout the Northern States. They saw their power waning, and this led them to encroach upon the prerogatives and independence of the Northern States by enacting such laws as the Fugitive Slave Law. By this law every Northern man was obliged, when properly summoned, to turn out and help apprehend the runaway slave of a Southern man. Northern marshals became slave-catchers, and Northern courts had to contribute to the support and protection of the institution.

Note that, in Grant’s telling, it was the Southern slave states that breached the federalist bargain by attempting to force the North into complicity with the institution. Not just acceptance, which Grant was at first willing to abide, but active reinforcement. Indeed, in the 1856 election, Grant supported the slave-state-preferred Democrat James Buchanan for President in the hopes that four more years of civil debate would avert secession and, ultimately, Civil War.

This, I cannot resist the urge to interject, is akin to many conservatives’ belief that the issue of same-sex marriage cannot hold as a state-by-state issue and should therefore be resolved at the national level in favor of current law, cultural tradition, and majority belief until such time as contrary belief has changed the culture sufficiently to explicitly rewrite the federal law. Of course, the issues are not exactly parallel, and it is fruitless speculation to suppose that U.S. Grant transplanted to the modern times would have accepted the progressive assertion that redefining the institution of marriage is “the civil rights issue of our day” in the way that throwing off the long history of slavery was in the 1800s.

Grant’s preferred priority, as suggested by statements peppered throughout his book, was maintenance of the civic structure that allowed the nation to address such fundamental differences peacefully through a political and social processes. While writing of his activities before the war, Grant notes that slavery ended with “four millions of human beings held as chattels hav[ing] been liberated,” and also with people “just as free to avoid social intimacy with the blacks as ever they were.”

That is a view most closely associated with the modern Right, and it’s starkly at odds with the present view of the Left that “civil rights” are those policies on which no vote should be held and for which no contrary behavior in any corner of the nation should be tolerated.