Things We Read Today (34), Monday

Moving the Machine Versus Keeping the Machine Mobile

When it comes down to it, there are basically three visions of the future guiding politics today. (Consider “in my opinion” to be implicit in my statements, here.) Probably the great mass of Americans think the United States will amble on toward prosperity, because that’s what the United States does, and they vote based on the aesthetics of social issues or based on general branding clichés like “the Democrats are for the working man” or “the Republicans are the party of enterprise.”

Between those who take a more ideological (and detailed) view, the remarkable thing is the different angles at which the political beast is viewed. Progressives see a march toward some future that is, for them, more or less defined, and they see the great arc of history moving toward it. The reelection of President Barack Obama means the march forward will continue; indeed, locking in a Democrat majority by one means or another will ensure the march for even longer. There will be difficulties, problems, and backslides, of course, but that’s part of Progress. Roll the machine to the next square on the board, modify what needs to be modified, and move on.

Conservatives tend not to operate on that level of faith in worldly affairs. They’ve looked at the machine and the unpredictable nature of reality, particularly in the context of the long, slow evolution of human nature that made advanced civilization possible, and with due consideration of all of the moving parts that can’t keep moving as they have.

Progressing to the next square can begin to leave important components behind, and even assuming the whole thing doesn’t explode, rebuilding will be a difficult, painful process. Better to deal with ever-changing reality by letting the natural mechanisms that have advanced humanity continue to work. The election of Mitt Romney wouldn’t have been a step toward a better future, but it would have been a marker that Americans are beginning to see the problems with Progress as it’s been defined.

Bubbles, Bubbles, Everywhere

As a conservative, myself, I find the compounding bubbles that have been emerging in the social-civic-economic fabric to be disconcerting. It wasn’t surprising that there was a dot-com bubble, a decade and a half ago, because the Internet was new. With chewing gum, it’s easier to make bubbles with a fresh piece.

The housing bubble of our current woes surprised more people, because housing and financing of housing is not new. In that case, the easing of risk in lending and innovative financial instruments were like a fresh piece of gum added to a long-chewed wad.

The bubbles that we conservatives see preparing to pop, now, are a bit different. They’re all slow-building: the entitlement bubbles, the higher education bubble, the lower education bubble, the pension bubble, the government bubble.

In Saturday’s New York Post, Jonathan Trugman added a new one to the list — the bond bubble:

… For generations, investors have looked to US bonds/Treasuries as “low-risk” savings instruments, almost like a bank CD. Bond losses were always something that happened in other countries like Argentina, Greece or Portugal, not America.

It is not as complicated as some would pretend, but it is extremely important for all to understand — especially those planning on retiring soon. Pension plans, 401(k)s, annuities, IRAs — retirement vehicles have never been more at risk than they are now.

The problem is that the price of a bond moves inversely to its yield; yields are interest rates, and they are at historical lows, meaning that they are likely to go up, making bonds worth less. Of course, rather than trading bonds, one can hold them to maturity, but then inflation takes its toll. And with the Federal Reserve pouring dollars into the economy via quantitative easing, inflation is a frightening specter, indeed.

As Trugman puts it, “the Fed has forced the bond market into unchartered and very unsafe waters.”

Making the Unsafe Safer at Others’ Expense

It’s not quite a bubble, but a renewed push for a national disaster-insurance pool would produce little more than a subsidization of communities in at-risk regions at the expense of those in safer regions, regardless of things like income and national benefit from populating risky climes.

The costly destruction of superstorm Sandy has inspired Florida members of Congress to make renewed attempts to create a national insurance pool to finance disaster recovery — and to help drive down costs for homeowners. …

Proponents say a national insurance plan would spare taxpayers the brunt of [disaster relief] costs while making homeowner insurance more affordable, especially in storm-prone places such as Florida. Consumers in the state would save on average $535 a year per household, according to a 2010 estimate by Milliman Inc., an actuarial consulting firm.

Southern shore states like Florida would be the top tier of beneficiaries from such a pool. One could see Northern shore states from Maryland through Maine as a second-tier region with lower risks. As printed in the Providence Journal, William Gibson’s McClatchy News Service article doesn’t cite anybody making the objection, but it should at least be asked why Americans who choose to live elsewhere should be on the hook for the expected calamities in the red and orange zones.

There are a multitude of reasons that people move to areas that experience fewer natural disasters, but a significant one is that it’s less expensive to live and do business there, now that transportation and interior climate control have advanced as they have. Why should the federal government make them buy into a global risk pool that doesn’t apply to them? Such differentiation is a major reason that we have a federal government system.

The Most Dangerous Pop

Of all the bubbles currently haunting the American mind (at least those that are haunted), the most dangerous is likely the size-of-government bubble, because the fumes filling that one are most dramatically a blend of power and money. As it grows, the likelihood of social collapse and or violent throes increases.

Citing the D.C.-as-Hunger-Games analogy, Glenn Reynolds writes in USA Today:

Washington is rich not because it makes valuable things, but because it is powerful. With virtually everything subject to regulation, it pays to spend money influencing the regulators. As P.J. O’Rourke famously observed: “When buying and selling are controlled by legislation, the first things to be bought and sold are legislators.” But it’s not just bags-of-cash style corruption. Most of the D.C. boom is from lobbyists and PR people, and others who are retained to influence what the government does. It’s a cold calculation: You’re likely to get a much better return from an investment of $1 million on lobbying than on a similar investment in, say, a new factory or better worker training.

So Washington gets fat, and it does so on money taken from the rest of the country: Either directly, in the form of taxes, or indirectly in the form of money that otherwise would have gone to that factory or training program.

Reynolds’s solution, like mine, is to begin pushing power back to the states as described in the U.S. Constitution. At that level, the fingers of corruption are easier to spot, and their prestidigitation is less contagious across the country — not the least because the national population can compare the results of each state’s policies and seek to emulate or avoid them. Only by federal fiat, for example, are states in the saner regions of the country apt to copy the governance models of Rhode Island and California.

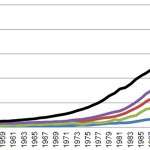

Frighteningly, though, nationalization of that blue-state approach appears to be continuing at the pace of an avalanche. Having observed the visible transition toward wealth from the window of a train headed into Washington, D.C., Reynolds would surely not be surprised by this graph, which appeared in the Sunday Providence Journal. It shows annual wages in government in Rhode Island climbing at a steady pace over the last decade, increasing the gap between it and other industries.

At some point, this trend cannot continue, and examples from elsewhere in history and elsewhere on the planet even now suggest that when capacity is reached, deflation of the bubble is much less likely than an explosion.