The Challenge of Getting Back to Basics in Education

Two Washington Post articles in the Fall River Herald seem to have similar themes, even beyond the fact that they’re both about education. The first, by Education Columnist Jay Mathews is about secondary school and the dearth of reading and writing:

The following statement is not a joke: Many writing classes discourage much writing. The nonprofit Education Trust found that only 9 percent of 1,876 literacy assignments in six urban middle schools asked students to write more than a single paragraph. Fitzhugh’s 2002 research found that 81 percent of high schools never assigned a paper of more than 5,000 words.

Sadly, English teachers don’t have time to handle lengthy researched essays. They cringe at what [Concord Review editor Will] Fitzhugh calls his Page Per Year Plan: a five-page paper in fifth grade, adding a page each year until everyone does a 12-page paper in 12th grade. He wants students to address issues they have read about, maybe even tackling a nonfiction book or two, very rare in schools.

One gets the sense that way too much is crammed on the “must be touched on” list of topics to allow for the slow digestion of works read and the (often) even slower germination of ideas that students might have in response. I remember my disappointment, way back when, that the information that I’d picked up in school didn’t just stay in my head, because I’d gotten the impression that it should. Why work through all those various topics if I’m just going to forget the content, anyway?

Yeah, there’s that old standby about “learning how to learn,” but somewhere in that lesson ought to be an exercise of depth — something with more of the feel of an apprenticeship to writing than a quick-tip lesson in the practice. Maybe answering this omission is the motivation behind the fad of “senior projects,” but at best, those seem frequently to focus on doing something somewhat substantial (relatively speaking) rather than learning something substantial.

The core of the complaint in Mathews’s column is that our education system doesn’t leave open the time for the students or the teachers to dally, and one can’t help but feel that we cram too much in, not only of subject matter but of all the rest. Between the educators and the educatees, there are clubs, diversity trainings, public service requirements, non-educational assessments of students, bureaucratic boxes to check, and on and on.

That sense applies University of Kentucky professor John Thelin’s explanation for the explosion in the cost of college:

Another fundamental element of the college experience was different in the 1960s as well. Costs were low because what colleges offered to students – and how many students they offered it to – was far more limited. Even with the decade’s admissions expansion, state universities such as the University of Massachusetts and Rutgers in New Jersey each only had a total enrollment of about 6,000. And colleges spent little on students. They handled expanding enrollments by increasing the size of lecture classes or other expedient measures like adding bunk beds to double the capacity of dorm rooms. They offered little in the way of advising, career placement, activities outside the classroom, recreational facilities and mental-health services. …

In many ways, this skyrocketing debt exposed the paradox of student consumerism. Increased competition led college officials to conclude that increased spending for elaborate residence halls and recreational facilities was necessary to lure students away from the competition. But an education more like the one provided in the 1960s would have kept costs – and student debt loads – far more reasonable.

Thelin doesn’t bring in the full picture. Elaborate amenities (and the architecture of coddling) may be a route to draw students to a particular university, but those institutions have also taken the opportunity of all that subsidized and borrowed wealth to create reasons for spending. How many “diversity” bureaucrats work on the typical American campus, and how many would really be needed, even if we were to concede the value of their occupation? How many entire fields of study now exist with no practical application — years and years of courses that nobody in their right mind would have taken back when the burden was on them to come up with the money in the near term? So much mere stuff!

This conundrum will not easily be unwound, absent a calamity. To ensure an educational experience more like an apprenticeship to learning would require paying some teachers much more, both to attract the necessary talent and to give it space to operate. Not only doesn’t our unionized factory model allow such a thing, but our special-interest politicization of education leaves the public no confidence that additional resources won’t be diverted from an agreed-to mission. Similarly, to bring colleges back to providing a valuable service to students intent on capitalizing on the opportunity, those students would have to have more skin in the game, which would require draining the system of so much easily available cash and credit, which would mean that some young adults who aren’t prepared for work won’t be able to check the box.

In short, the incentive structures aren’t there for a systemic fix, which probably means that only those privileged few with the awareness and wherewithal to supplement the public offering will actually reap any lasting benefits from it.

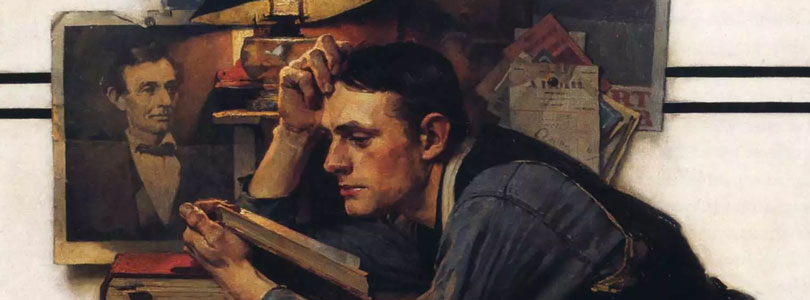

Featured image: Norman Rockwell’s The Young Lawyer.