State in Decline, Employment in RI Cities and Towns: East Providence

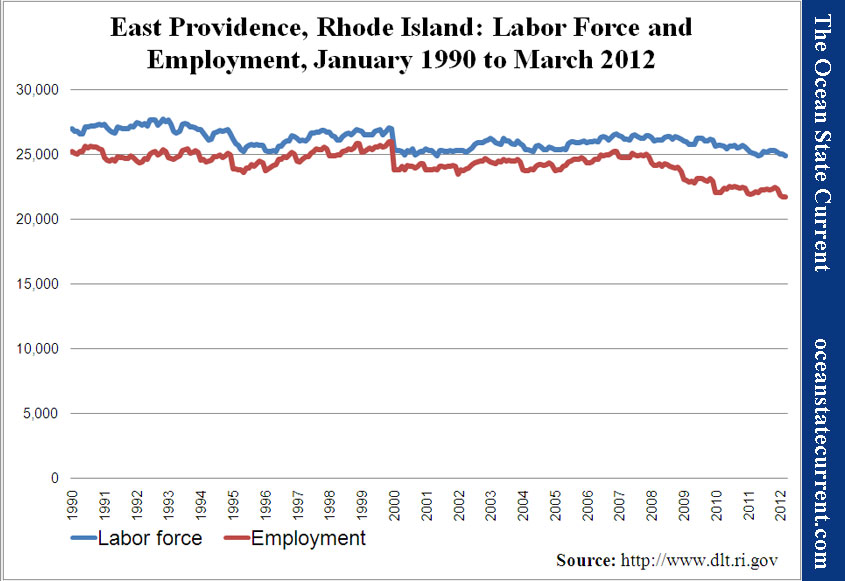

At 12.8% in March, East Providence’s unemployment rate is well above that of Rhode Island’s overall 11.8% (numbers are not seasonally adjusted). That difference results, in part, to the trendline that the town followed over the first decade of the century.

From 2000 the 2010, East Providence’s labor force (the number of people working or looking for work) grew 1.5%, but its total number of employed residents fell 6.9%. These numbers resulted even as the town’s total population fell 3.4%.

The chart below shows that the trends have been down from there. In March, East Providence’s total employment was the lowest that it has ever been in the twenty-two years of data that the RI Dept. of Labor and Training provides. The town’s labor force is also very nearly its record low for that period, making it all the more remarkable that the number of unemployed residents in East Providence is much closer to its maximum than its average.

Unemployment is represented in the chart as the space between the lines.

Note on the Data

The population data above comes from the U.S. Census conducted every ten years and is therefore generally considered reliable, to the extent that is used as reference for various government programs and voter districting.

The labor force and unemployment data, however, derives from the New England City and Town Areas (NECTAS) segment of the Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) of the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). A detailed summary of the methodology is not readily available, but in basic terms, it is a model based on and benchmarked to several public surveys. It can be assumed that the sample rate (i.e., the number of people actually surveyed) in each Rhode Island town is very small (averaging roughly 30 people per municipality).

The trends shown, it must be emphasized, are most appropriately seen as trends in the model that generally relate to what’s actually happening among the population but are not an immediate reflection of it. Taking action on the assumption that the exact number of employed or unemployed residents shown corresponds directly to real people in a town would vest much too much confidence in the model’s accuracy.

Be that as it may, the data has been collected and published, and taken a town at a time, it is relatively easy to digest. So, curiosity leads the Current to see it as the best available data to deepen our understanding of trends within Rhode Island. If the findings comport with readers’ sense of how the towns relate to each other, perhaps lessons regarding local and statewide policies may be drawn. If not, then the lesson will be on the limitations of data in our era of information overload.