Differing Interpretations of Tax Effects Play into Local Decision

Throughout the autumn and winter, the Occupy Movement filled newspapers with slogans pitting Americans from the top 1% in wealth against the other 99%, whom the Occupiers presumed to represent. That spirit has entered the General Assembly, this session, in the form of seven different proposals to increase taxes on “the rich.”

Advocates tout a paper released this month by Jeffrey Thompson, an assistant research professor with the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts. Reviewing research literature related to the effects of tax increases on wealthy residents, Thompson concludes that, in general, “modest tax increases on affluent households are unlikely” to change their economic behavior or drive them out of the state. It is more likely that they’ll find ways to avoid the increased taxes, but such results “are not nearly as dramatic as the consequences predicted by some.”

On the other end of the debate, the Rhode Island Center for Freedom & Prosperity (the parent organization for the Ocean State Current) expects significant consequences. Using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model developed by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University, the Center predicts that the most cited tax increase proposal would cost the state 1,372 jobs and 1,000 residents overall, while falling $13 million short of advocates’ $118 million revenue target.

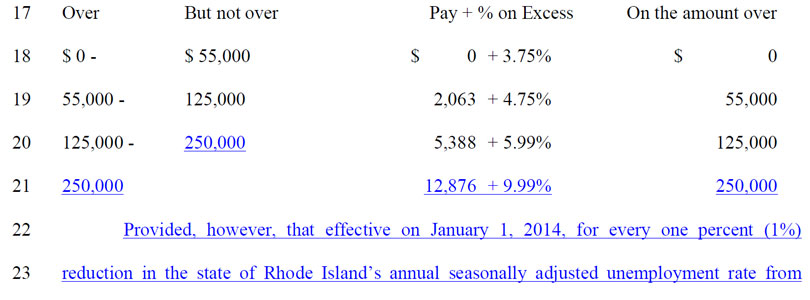

The various bills submitted into both chambers of the General Assembly would impose different increases on different income ranges. In the House, H7379 would add 1% to the tax on income over $250,000; H7305 do the same for incomes over $500,000. H7381 and H7382 would add 2% to those ranges, respectively. Meanwhile, H7913 would repeal the 2010 tax reform completely. In the Senate, S2246 would increase the tax on incomes over $500,000 by 3%. The largest increase would derive from H7454, which would add another 4.1% to the tax on income above $200,000.

The greatest attention, however, has been paid to legislation making its way through both chambers, as S2622 and H7729. These bills would create a new tax bracket for income above $250,000, increasing the rate by 4%, to 9.99%. That rate applied only to income over $373,650 prior to 2011. (The new bracket would affect approximately the top 3% of taxpayers.)

Governor Lincoln Chafee’s proposed budget for the fiscal year beginning in July increases spending by $241.5 million (3.1%). Of that increase, general revenue funding accounts for $163.3 million (a 5.1% increase from the prior year). The largest source of that additional revenue, beyond assumed economic growth, would come through increases in sales and use taxes, such as an expansion of sales taxes and a hike in the meals tax. Raising the income tax on high earners would either replace those revenue proposals or add to them.

According to the fiscal notes that the Rhode Island Budget Office prepared to accompany the four smaller House bills, the additional revenue anticipated for fiscal 2013 would range from $18.4 million to $65.3 million, depending on which one passed. However, the notes stress that the estimates “are static estimates and do not include any behavioral responses that might be engendered from the act.”

Advocates for the more expansive tax increase tied to unemployment, meanwhile, cite data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) claiming that the legislation would raise $118 million. That number, according to ITEP Executive Director Matthew Gardner, is also static. It is “not beyond the realm of possibility” that tax increases will change residents’ behavior, but such arguments inherently involve “conjecture.” Nonetheless, he says, “You want to have an open debate on every element of this.”

Jeffrey Thompson’s paper attempts to give substance to the conjecture by reviewing the “massive” literature on the subject. His findings therefore attempt to generalize the results of previous tax changes under very specific circumstances into broader principles. In some cases, those principles seem, he admits, “counter-intuitive.” For instance, he finds that “higher taxes lead to more new small business ventures and self-employment,” which is the opposite of the effect one would expect if wealthy entrepreneurs leave or restrain their activities.

“You can find these weird, spurious empirical relationships,” Tax Foundation Economist William McBride told the Current, “but that doesn’t mean they have any basis in reality or theory.” His colleague Scott Drenkard adds that “raising taxes on income is one of the more destructive ways that you can raise taxes, because you’re disincentivizing wealth creation and new value.”

Thompson’s paper notes that self-employment would include small, blue-collar tradesmen as well as trail-blazing entrepreneurs. Writing about hours worked, he suggests that taxpayers may actually work more in the wake of a tax increase in order to “maintain their… levels of consumption.” Therefore, one way in which his findings might align with Drenkard’s warning would be if higher taxes depress the economy, limiting opportunities for regular employment and forcing workers to set out on their own.

In that regard, the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity worries that “the message from this tax increase would be clear to businesses and individuals who have the mobility to move to or settle in other states … Rhode Island imposes a hostile level of taxes.” Whether or not the message is enough to dislodge residents who are already here, it may play a significant role in the decisions of people and businesses that are facing changes anyway.

Whatever the direction of their conclusions, all of the national experts appear to agree that taxation must be considered within the circumstances of the state. Residents may accept a greater tax burden in exchange for better services or as part of an explicit effort to turn a declining state around. How those factors balance out is a subject for public debate.

“It’s not that we are necessarily against higher taxes,” wrote Cranston resident Jennifer Hushion in a recent op-ed for the Current. But the services her family receives aren’t adequate, she says, whether the educational opportunities for her son or the maintenance of the roads. Moreover, “My family only sees the situation getting worse.”