Robbing productive class Peter to pay college graduates Paul

Is the departure of recent college graduates keeping Rhode Island at the back of the pack economically? Progressives in the state’s legislature apparently think it would be beneficial to have taxpayers subsidize student loans. A look at student debt data suggests that would be a major burden on a population that’s already heavily taxed–and that the idea may, in fact, backfire.

The debate has been raging almost since the turn of the millennium: With Rhode Island’s population waning, who’s leaving? The first assumption was that the rich were fleeing the high taxes, which inspired policies meant to keep them — like an alternative flat tax and a phase-out of the capital gains tax.

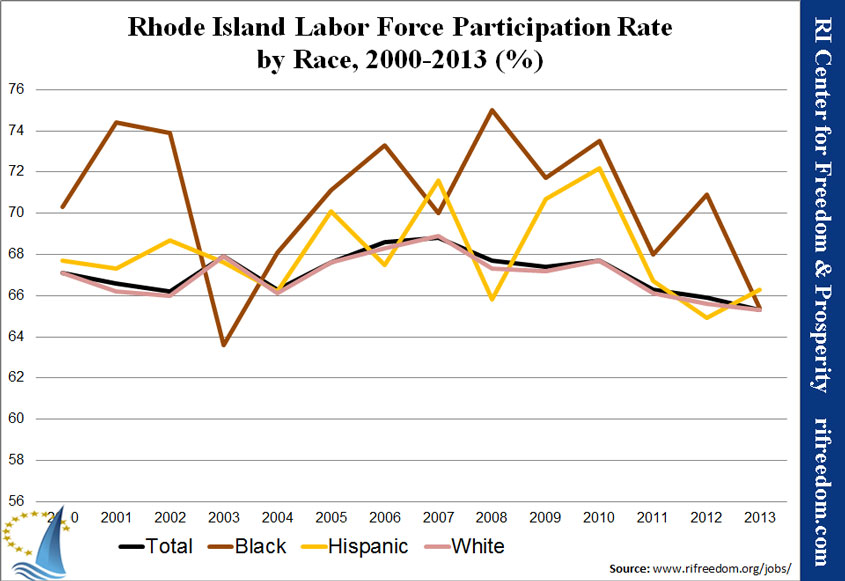

Progressives objected that the evidence did not show flight of the rich, and as it turned out, they were right. The departing demographic was the “productive class” — families in that highly motivated period of their lives when they’re exchanging their time, sweat, and talents for a trip up the rungs to the middle class.

To make that group stay, though, politicians can’t cut taxes in exchange for the campaign support like do for the wealthy. And the productive class doesn’t use direct government handouts, so the government can’t make them stay by handing out entitlements. They need less regulations so they can work and innovate, and they need to be able to keep the money that they’ve earned, rather than having it taxed away.

If we look at who is sponsoring two relevant pieces of legislation on the subject, it becomes clear that Rhode Island progressives have decided to try and bribe recent college graduates into staying in the state. Based on the rationale described in the bills, they hope a younger crowd will be like their older brothers and sisters in helping the economy to grow.